0006. A Treatise on African Art: The Art and Legacy of the Maghreb

- Afrilenstories

- Jun 7, 2025

- 5 min read

The Sahara Was Once Green

LONG before the Sahara became the world’s largest hot desert—a parched and blistering expanse of sand stretching from the Atlantic to the Red Sea—it was a vast, lush savannah.

Rivers carved through valleys. Grasslands teemed with giraffes, elephants, and crocodiles. Around 11,000 BCE, this verdant world was home to early human communities who hunted, herded, painted, and prayed under starlit skies.

But by 3,000 BCE, climate patterns had shifted. What was once a flourishing garden of Africa dried into dust. The desert began its slow, stubborn conquest of the central heartlands. And the people? They moved—north toward the coastlines, east toward the Nile, and south toward the Sahel.

That arc of land to the northwest, which remained green and generous, came to be known by its Arabic name: al-Maghrib—the land of the setting sun.

The Imazighen: Free People of the Maghreb

The inhabitants of this land were not a nameless, faceless mass. They called themselves Imazighen—the “free people.” But outsiders, from the Greeks to the Romans, dubbed them “Berbers,” a corruption of the Greek barbaroi, or “barbarians.” A misnomer that stuck like a colonial echo.

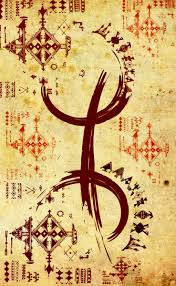

Yet the Imazighen endured—and thrived. Their languages belong to the Afro-Asiatic family, cousins to Ancient Egyptian, Arabic, Hausa, and Amharic. They passed down stories and spirits, threading identity into body art, silver jewelry, tattoos, textiles, ceramics, and the rhythmic architecture of their mountain towns.

They left us more than names. They gave the continent the legacy of Amazigh art—a cultural memory that stretches from the stone tombs of Mauritania to the rock paintings of Algeria, and all the way to the high desert cities of Morocco.

Whispers from Stone: The Rock Art of the Central Sahara

If walls could talk, the sandstone cliffs of the Tassili n’Ajjer plateau in southeastern Algeria would whisper the oldest stories of the Sahara. Here, thousands of rock engravings and paintings mark the timeline of human presence—vivid, spiritual, and astonishingly well-preserved.

Art historians like Frank Willett and Monica Visona have mapped these visual echoes into distinct periods:

The Large Wild Fauna Style (c. 8000–4000 BCE) In Fezzan, Libya, life-sized depictions of giraffes, buffalo, elephants, and lions dominate the scene. Made with stone tools and abrasives, these works suggest a thriving, animal-rich ecosystem before the desert’s arrival.

Archaic Paintings Found across the Sahara—chalk and ochre outlines of human and animal forms, sometimes ghostlike, always grounded in the earth’s pigments.

The Pastoralist Style (from 5000 BCE) As herding culture spread, so did a new visual language: cows, sheep, and goat herders appear in ochre-red and carbon-black silhouettes, often painted with a mixture of pigment and cow’s milk—a fitting tribute to their livelihoods.

Horse and Chariot Period (c. 2000 BCE onward) Even as the desert took root, the artistic pulse continued. Scenes of horses, chariots, and warriors—often associated with the semi-nomadic Imazighen—spread across rock faces from Egypt to Morocco. These artworks tell of movement, trade, conflict, and resilience.

The Maghreb Meets the Mediterranean

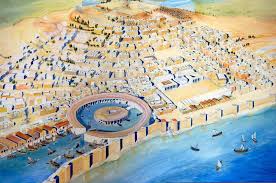

As the sands expanded, the Maghreb remained a cradle of interaction—a crossroads between Africa and the Mediterranean world. The Phoenicians founded Carthage in present-day Tunisia, building a commercial empire that would rival Rome itself. In Libya, Greeks established Cyrene around 631 BCE, a city of columns and learning perched on a limestone plateau.

By the 2nd century BCE, Amazigh rulers like Massinissa and Juba II had risen to power in Numidia and Mauretania. Juba’s royal tomb—known today as the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania, near Tipasa, Algeria—is a stunning stone tumulus blending Roman, Berber, and Hellenistic elements. It was built for him and his queen, Cleopatra Selene, the daughter of Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony. A marriage of Egypt, Rome, and North Africa etched into stone.

Further inland, Roman towns like Timgad (Thamugadi) rose along imperial roads. Founded by Emperor Trajan in 100 CE, this was no mere outpost—it had public baths, a forum, a library, and a perfect Roman grid. It was built atop Numidian soil, near Juba’s tomb, a reminder that the story of empire always begins with land that belonged to someone else.

Even the emperors carried Maghrebi blood: Septimius Severus, who ruled Rome from 193–211 CE, was born in Leptis Magna, Libya, and claimed Amazigh ancestry.

The Islamic Tapestry: Mosques, Dynasties, and Almoravid Glory

The Islamic conquest of North Africa in the 7th century CE brought sweeping changes. Cities like Timgad faded into memory. The Vandals had come and gone, the Byzantines had tried to hold on, but now the Maghreb was part of a new world—the world of Islam.

In Kairouan, Tunisia, General Uqba ibn Nafi built one of the first great stone mosques around 670 CE. After rebellion razed it to the ground, the Aghlabid Dynasty rebuilt it in 836 CE. That mosque still stands today—a monumental anchor of Islamic architecture, influencing later mosques from Fez to Timbuktu.

By the 11th century, Amazigh groups like the Almoravids—fierce and faithful—emerged from the southern Sahara (present-day Mauritania). They swept north, toppling corrupt emirs and conquering Morocco, Algeria, and Islamic Spain. In just two generations, they ruled from the Senegal River to the Ebro River in Spain. Their capital, Marrakech, became a cultural hub. And in Fez, they protected and expanded the Qarawiyyin Mosque, which still serves as one of the oldest universities in the world.

Amazigh art in this period turned increasingly abstract and symbolic—in part due to Islamic prohibitions against figural representations. The result was a focus on geometry, symbolism, color, and texture—a quiet yet powerful resistance through beauty.

Echoes in Earth and Stone

From the troglodyte caves of Matmata in Tunisia to the Kabyle pottery, fortified ksour of Morocco, and the silverwork of Tuareg nomads, the Maghreb is a tapestry of cultural memory. Leatherwork, textiles, personal adornment, and even nomadic tents preserve what the desert has not erased.

In Chinguetti, Mauritania, once a holy city of desert scholars, libraries still hold medieval manuscripts. The stone houses there mirror the lost architecture of Kumbi Saleh, the capital of the Ghana Empire, bridging Islamic and Amazigh worlds.

Final Thought: The Sahara Remembers

In the sandstone silence of the Tassili, you can still find ancient cattle painted on rock, humans in procession, hunters mid-leap. Archaeologists estimate the first settlements here date to c. 5450 BCE, and the earliest paintings followed soon after.

They remind us: the Sahara was once alive with water, animals, and art. And the Maghreb, ever adaptive, still speaks the language of resilience. In every silver earring, mosque archway, or ancient stele, the Imazighen whisper: “We were here. We are here. We will remain.”

As we share this African art corpus, we express our deepest gratitude to great art historians, like Frank Willett, Peter Garlake, Dennis Duerden and Monica Visona; whose works have formed the foundation of this story. On other online sources we also relied.

Coming soon: East African Art.

Part of this writing was contributed by Denis Chiedo.

Comments